My husband, Trever, eats peanut butter and jelly every day for lunch. This isn't just any ordinary peanut butter and jelly though - it's a gourmet PB&J. Here in Virginia, going to farms to u-pick peanuts is a thing (have I mentioned there is a pork, peanut, and pine festival every fall to celebrate just that?), and we'll stockpile peanuts to grind our own peanut butter. Additionally I will make jams, jellies, and preserves throughout the year for him to use - his favorite being vanilla-fig jam (which came as a surprise to both of us). Finally, to make the experience truly gourmet - we will make the sandwich bread ourselves. Since homemade bread can go stale quickly, this means we end up baking mini-loaves of bread 2 or 3 times a week - which makes our home smell like heaven, and there is nothing quite like fresh baked bread to make your house smell like a home.

What is Yeast?

Yeast is a living cell that feeds off of sugar to ferment during the rising process, which yields an end product that is fluffy and light. Without yeast, dough will come out flat and resembling something more like a cracker. Yeast has been around since the ancient Egyptians time, but the first published by French microbiologist Louis Pasteur in the mid 1800's. Pasteur is most famous for his development of the process of pasteurization, which kills living organisms in foods like milk or beer.

Advancements in Yeast

Have you ever made friendship bread? You know the one I'm talking about, where someone gives you the bread starter and you add a few ingredients, let them sit for a couple days, remove a small amount to pass on to friends so they can make the bread as well, and then use the rest to make the dough. That's the one! The starter for friendship dough is a liquid starter (just like sourdough), and that is how yeast used to be used and sold until about 1825 when some scientists figured out how to remove the liquid so yeast could be distributed as paste or solid compressed blocks, which is how fresh yeast is still sold today.

Somewhere around the mid-to-late 1800's a filter was created that removed the liquid and allowed manufacturers to create a granulated product - resulting in the kind of yeast that we primarily use today.

Different Kinds of Yeast

The key to understanding yeast is to know which kind to use, and how each behaves.

- Fresh Yeast. While uncommon, some professional bakers still prefer working with the real deal. It has a relatively short shelf life and is usually acquired in 1 pound blocks that are damp and pasty.

- Active Dry Yeast. This is a granulated form of yeast that needs to be dissolved in water to be used. This is the kind I use at home, and also the kind that most recipes call for. You can purchase it in jars, boxes, or handy individual size packets -though that tends to be more expensive. Usually, active dry yeast needs four times its weight of warm water to by rehydrated, and the ideal temperature of the water is 110°F. If your recipe calls for more water or liquid than that, use just four times it's weight for dissolving and add the rest after the yeast has activated.

- Instant Dry Yeast. Also a granulated yeast, instant yeast absorbs liquid much faster than active dry yeast, so it does not need to be activated in water and can be added directly to your dry ingredients instead. Also known as quick-rise yeast, bread-machine yeast, or rapid-rise yeast, instant dry yeast produces more gas during the rising process than active dry yeast, so less can be used, and rise times can be cut in half. Instant yeast needs higher temperatures than active dry yeast to activate - somewhere between 120°F and 130°F.

Surprisingly enough, the substitution amounts of active dry yeast and instant yeast are heavily argued. Many people agree that a 1:1 ratio can be used, making each work interchangeably, but many people will argue that up to 25% less instant yeast should be used when substituting to get a similar end product. I'm a little old fashioned and work primarily with active dry yeast, so this isn't a predicament that I run into, but on the odd occasion where a recipe calls for instant yeast, I personally tend to measure out the same amount in active dry yeast.

Other Kinds Of Yeast

There are a few other types of yeast out there that are well known, but are not leavening agents.

- Brewer's Yeast. This is a heat treated yeast that is no longer living, therefore unable to work as a leavening agent. Brewer's yeast is a complete protein that is easily digestible, great for making beer, and often used to help stimulate milk production in lactating women.

- Yeast Extract. This is a yeast that has had the cell walls removed and is used as a flavoring for foods like vegemite and bovril. Many manufacturers of packaged foods will use yeast extract (which contains glutamic acid) in place of MSG because it almost the same thing but does not have the stigma of MSG.

- Nutritional Yeast. Popular amongst vegans and vegetarians, nutritional yeast is an inactive yeast that many people will use as a cheese alternative. It has a slightly nutty flavor and is also popular as a topping for popcorn or mixed into mashed potatoes.

How To Use Yeast

Like anything, there are a few key thinks to know to make yeast work well. let's take a look.

- Time. In order for the yeast to ferment and really do its job, you need to give it enough time to rise. If you are making a whole wheat dough, you may want to give yourself a little extra time so you can let it rest if you over-activate the gluten or it didn't rise enough. Depending on which kind of yeast you are using, you may need more time than with others; active dry yeast needs more time, and more risings than instant yeast requires.

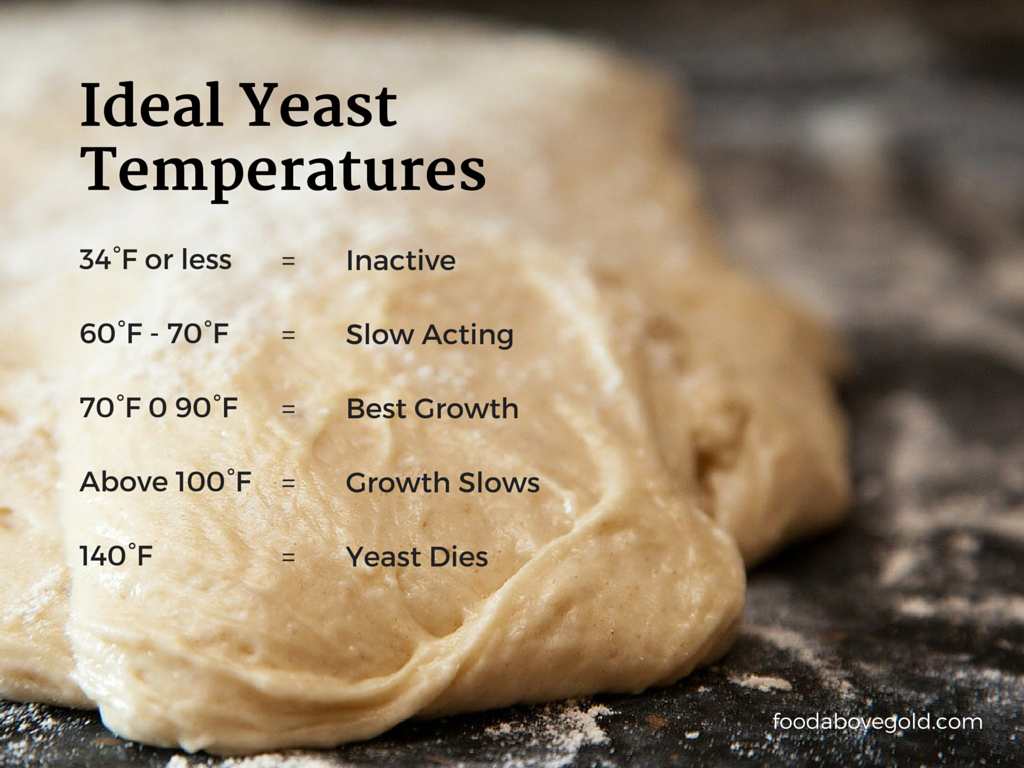

- Liquid Temperature. Proofing yeast is the process of activating the yeast - if you've worked with yeast before you will recognize this as the point where the it gets foamy. The temperature of the liquid you are proofing your yeast in is very important to your success. If it is too cold, the yeast won't activate and you'll end up with it not rising while it rests, but reacting when it cooks in the oven. If it is too hot, it will kill the yeast altogether, which results in a dense, flat, and tough dough. Active dry yeast needs the liquid to be ideally around 110°F while fresh yeast needs only 95°F to react.

- Sugar/Sweeteners. This plays double duty. In order for yeast to work its best it needs something to eat, and yeast prefers sweet things. Most recipes will use granulated sugar, but this can be achieved just as well with honey, molasses, or alternative sweeteners like stevia. Additionally, if you are sure your water temperature is at 110°F when activating, if the yeast does not proof with the addition of sugar, it may be an indication that it has expired. This is a basic part of the process with active dry yeast, but if you are using instant yeast and suspect it may be a little far gone, stir together a pinch of sugar, a pinch of yeast, and about a tablespoon of lukewarm water and let it sit for a few minutes. If it doesn't become foamy, then your suspicions were probably correct and it is time to buy new yeast. If it does become foamy, you are good to add it (not proofed) into your dough and can be confident that your bread will rise. I recommend doing this every time you use instant yeast so you don't get to then end and become frustrated that your bread didn't rise.

- Other Ingredients. Make sure that all the ingredients you put into your dough are at room temperature. If you add in milk, eggs, or butter that is straight from the refrigerator (just like with boiling water) it will drop the temperature of the dough. Since the goal is to keep the yeast alive, temperature range is extremely important and you do not want to drop it below and risk making your yeast inactive. Also, the more ingredients you add, the slower the dough may rise. As the yeast ferments and creates carbon dioxide, that gas has to develop against the pressure of the ingredients. The more ingredients there are, the more the yeast has to work to create and distribute the gas.

- Warmth for Rising. You may recall your grandmother making bread and setting it on top of a wood stove, heater, or in the sun to rise. This is because heat helps the yeast work, just like it helps it activate. Dough will rise well enough at room temperature, but if you want to cut down the time it takes put the dough to somewhere where the temperature is between 80°F and 90°F. If you choose to set it directly on a heat source (I place it on top of a heating grate in the winter) make sure to put a towel between the heat source and the bowl to prevent the dough from starting to cook - which will make the dough dry and the yeast less effective. The warmer the dough, the faster it will rise, but let it get too hot (140°F or higher) and it will kill the yeast.

How To Store Yeast

If you are a die-hard purist and use fresh yeast, make sure to keep it refrigerated and use it within about two weeks or by its best-used-by date. Some people will purchase fresh yeast and cut it into sections to freeze, but I find that in the process of freezing and thawing, fresh yeast loses some of its potency. If you have granulated yeast though, you have a little more time. Granulated yeast can be kept at room temperature until the container is opened. Once it is opened store it in an air-tight container in the refrigerator (below 35°F) for up to 6 months or until the best-used-by date. Make sure as you start to approach that date to double check your yeast by proofing it to make sure it hasn't gotten too old.

Yeast in Veganism

Every summer Trever and I pick one new thing to try, and the summer before we got married we decided to go vegan. It gave us something to share and talk about from 3000 miles apart. One of the conversations we had was about yeast because whether or not yeast is vegan is a heavily debated. As mentioned earlier, yeast is a micro-organism, a cell, so by some people's definition of veganism, that means that anything that contains yeast goes against the vegan way because you are killing a living organism. Others argue that because yeast can not experience pain, it makes it more like a fungus, therefore, absolutely okay in the vegan diet. When it comes to understanding yeast, this is one you'll have to decide for yourself, but I personally would be sad to miss out on beer and wine.

Phew...that was a LOT of information, but hopefully you feel prepared to make stellar dough from here on out!

If you'd like to put all of this into practice, you can go try it with a few of our recipes like:

What are your thoughts?